Understanding Children’s Drawings: Emotions & Family Insights

2025-08-16 12:00:49

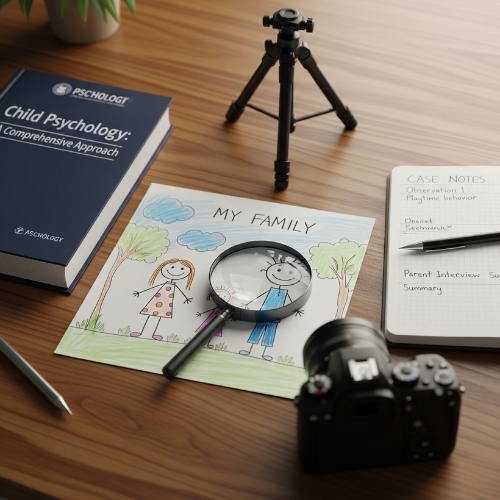

Children’s drawings can provide a fascinating window into how kids perceive and represent their world. They are also valuable tools for therapists, as children sometimes find it easier to express themselves through images than words. But do children’s drawings, by themselves, indicate that something is wrong? Research strongly suggests not.

Imagine a stack of drawings created by 6-year-olds asked simply to “draw a family,” with no other instructions. As you go through them, many children produce colorful, detailed, and cheerful images. Family members are smiling, placed front and center, and drawn with roughly correct proportions, each with distinct characteristics. These drawings convey feelings of belonging, pride, or happiness.

Yet a few drawings may appear bleak, distant, or lonely. Some are colorless despite access to crayons, with figures looking unhappy or oddly distorted. Family members might be separated, missing entirely, or crowded into a corner. Human figures may lack arms, hands, or faces, or features that differentiate one member from another. Such images raise questions: Do they reflect stress at home? Are they warnings of potential difficulties?

Interpreting Children’s Family Drawings

Research across multiple cultures shows that family drawings can reflect children’s perceptions of family life, but with important caveats:

- Drawings are not proof of a problem. They may offer hints or clues.

- Skill level matters. Children vary widely in their artistic abilities; a lack of detail might simply reflect developmental stage.

- Cultural context is critical. In Western societies, smiling faces and parents next to children are expected. But among the Nso farmers of Cameroon, children often draw people without smiles or even mouths, and may depict non-parents as central figures. This reflects cultural norms of emotional control and caregiving practices rather than insecurity.

Thus, developmental skills, cultural norms, and childrearing practices must be considered. Media exposure, personality, and even temporary moods also influence children’s drawings. To paraphrase Freud, sometimes a drawing is just a drawing. Psychologists rarely make judgments based solely on children’s artwork—they require additional context.

Evidence Linking Drawings and Family Life

Long-term research, such as the study by Bharathi Zvara at the University of North Carolina, followed over 900 children from infancy through first grade. Researchers observed children at home, noting maternal behaviors and household “chaos” (disorganization, instability, noise, clutter, inconsistent routines). When children were six, they drew family pictures, which were analyzed for:

- Lack of family pride: Missing smiles, dull colors, or isolated family members.

- Vulnerability: Distorted self-depictions or exaggerated body parts.

- Emotional distance: Negative expressions or separation of family members.

- Tension/anger: Careless execution, lack of color or detail.

- Global negativity: Overall impression of disorganization or gloom.

Results indicated modest but significant correlations: children with warm, sensitive, and stimulating caregivers tended to produce happier, more cohesive family drawings. Harsh or controlling parenting, or high household chaos, correlated with more negative, alienated images. When researchers controlled for maternal behavior, household chaos alone no longer predicted the drawings.

Thus, family drawings reflect parenting style to a small extent but are not definitive proof of dysfunction. An unusual or emotionally negative drawing may suggest—but does not confirm—stressful or harsh parenting.

Drawings and Other Psychological Measures

Family drawings, sometimes called the “Family Drawing Paradigm” (FDP), are increasingly used to assess attachment when verbal communication is difficult, and are less stressful than the “Strange Situation Paradigm.” However, evidence suggests FDP is not a highly accurate indicator of attachment. For example, in one study of 41 children (ages 5–8), FDP results did not align with Strange Situation outcomes.

Similarly, drawings alone cannot confirm trauma or abuse. A 2012 review by Brian Allen and Chriscelyn Tussey found the literature inconsistent and methodologically flawed. More recent studies (post-2012) suggest certain patterns in self-portraits of victimized individuals may be indicative, but correlations are imperfect, and drawings cannot be taken as proof.

EN

EN

Your Comment

Understanding Children’s Drawings: Emotions & Family Insights